A Woman & Her Legacy: A Brief History of Margaret Morrison

Last year marked the 50th anniversary of Carnegie Mellon University. Notably, 2017 was also the first time female students make up a majority of first-year undergraduates. At fifty-one percent, the proportion of women is much higher than the national average for peer institutions. This tipping point may surprise some. But if you’re a campus history enthusiast, you might have seen it coming.

Women have made their mark within the Carnegie Mellon community since the university’s founding. Even before Andrew Carnegie and the Mellon brothers merged their respective institutions in 1967, women’s education played a central role in shaping Carnegie Tech’s campus, curriculum and legacy. Moreover, our mission to “attract and retain diverse, world-class talent” has reinforced the commitment to supporting outstanding women across disciplines.

After spending 2017 honoring our three male founders, Andrew, Andrew, and Richard, we would be remiss not to recognize the strong female leaders, students, and professors who have shaped and strengthened our community. Margaret Morrison, Andrew Carnegie’s mother, was the first.

Margaret & the Maggie Murphs

Margaret Morrison was the mother of three children and the wife of William Carnegie. When William, a weaver, was having trouble finding work, Margaret took the initiative to move her family across the Atlantic Ocean, from Dunfermline, Scotland to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where her sisters lived. At thirteen years old, her son Andrew Carnegie started working as a bobbin boy at a Pittsburgh textile mill, where he would bring bobbins to the women at the looms and collect the full bobbins of spun thread. He was also self-educating himself at the library in the evenings. When Margaret passed away thirty-eight years later, Andrew had grown to become a successful telegrapher, railroad executive, entrepreneur and finally, steel baron.

When Andrew was contemplating his legacy and thinking about giving back to the community, he knew one thing: he wanted to honor his mother’s influence. He named one of the Carnegie Technical Schools that he founded in 1906 after his mother. Although there is not much information available about Margaret’s early life, it was well known that Andrew adored her. In a letter to the Board of Trustees, Andrew wrote that he cherished Margaret as the person “to whom [he] owes everything”.

Margaret Morrison Carnegie School for Women became one of four schools offering two-year certificates and three-year diplomas to students and working professionals from Pittsburgh and neighboring towns. In contrast to the “Seven Sisters,” the elite, all-female liberal arts universities in New England, Carnegie placed a greater focus on trade studies.

The women of Margaret Morrison, also known as Maggie Murphs, started taking classes in Porter Hall, until their new building was completed in 1907. Originally, the school offered only vocational courses that trained women to be librarians, secretaries, seamstresses, and bookkeepers. However, it didn’t take long for the curriculum to evolve in response to female student demand. At a time when American women still didn’t have the right to vote, these changes were a harbinger for the way in which a woman’s role would transform in society over the next century.

Expanding women’s curriculum

Between 1906 and 1912, new courses were introduced across disciplines. According to Edwin Fenton’s book The Maggie Murphs, a 1912 academic report described “new courses in inorganic and physiological chemistry, new literature and history courses in which students read the Iliad and the Odyssey, a new emphasis on biological and cultural development of the family, new courses in psychology and French, and the development of an option in teacher preparation.” When Carnegie Technical Schools changed its name to Carnegie Institute of Technology in 1912, Margaret Morrison Carnegie School for Women became Margaret Morrison Carnegie College, offering traditional four-year degrees.

Between 1912 and 1967, the school classes and offerings were increasingly integrated into Carnegie Institute of Technology. The closing of Margaret Morrison Carnegie College in 1973 marked the opening of the College of Humanities and Social Sciences and the full integration of women into the larger university. Since then, the historic Margaret Morrison Carnegie Hall building has housed students and faculty in the Public Policy, Drama, Architecture, Music schools and now is home to the School of Design.

Women of Margaret Morrison Carnegie Hall

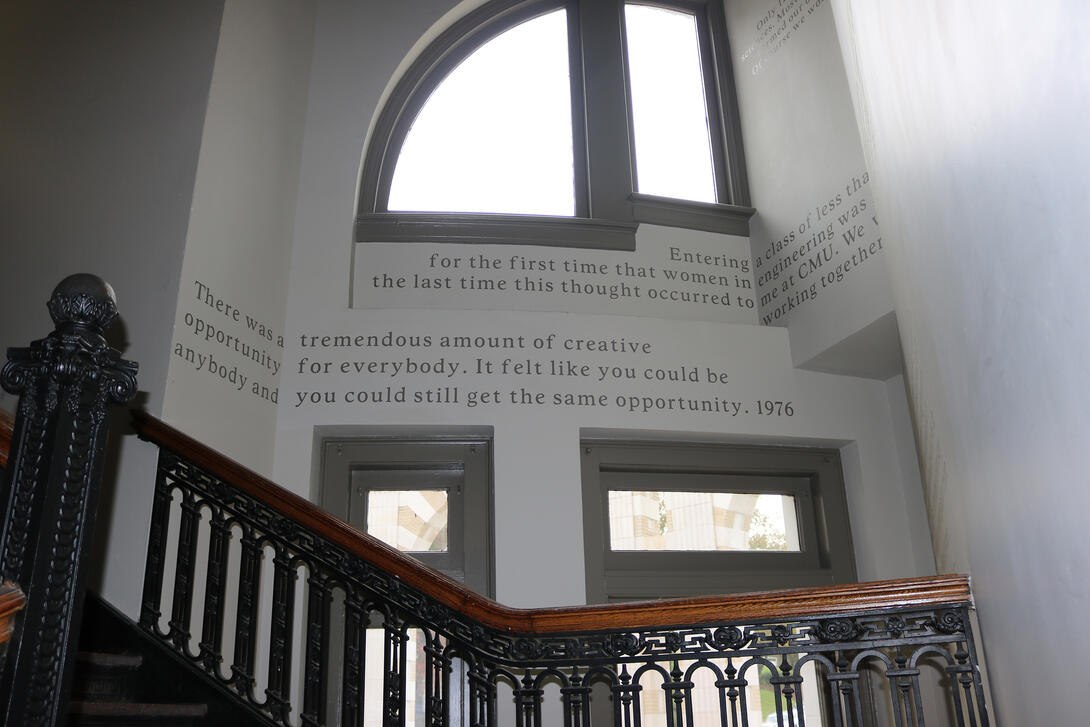

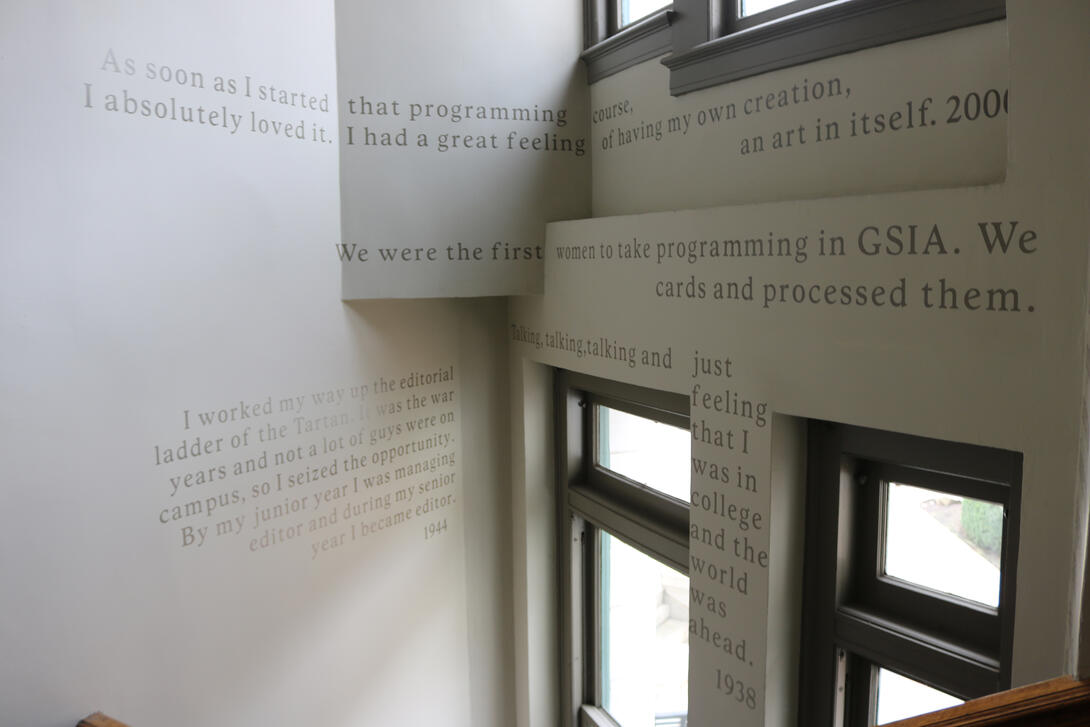

Today, Margaret Morrison Carnegie Hall is recognized on campus as the women’s building. The entrance features a large portrait of Margaret and the stairwells are stenciled with quotes from female students throughout the history of Carnegie Tech and the Carnegie Institute of Technology. It is a place that women and men alike recall with admiration. The building is also a space that many alumni have returned to, in some form or fashion, as it rekindles memories of bright college years.

Bette Landish, a proud Maggie Murph and former educator who lives in Point Breeze with her husband Mark, started at Carnegie Institute of Technology in 1964, just a few years before the Mellon Institute merger. She entered the school as a Textiles and Home Economics major, switching later to study history. She recently reflected on the physical changes of the campus since she was in school, commenting on how “all the buildings were painted black” when she was in school because the “rough stone buildings would soak up the soot from the steel mills.” Bette shared a common affinity with the women who spent time learning in Margaret Morrison Carnegie Hall. “I fell in love with college,” she told me, “but mostly with CMU.” Bette returned to Carnegie Mellon for two additional degrees and admits that she was more comfortable at CMU than she’s been anywhere in her life.

Stacie Rohrbach attended Carnegie Mellon as an Bachelor of Fine Arts (BFA) undergraduate in 1992, returned in 2003 as an Assistant Professor, and became a tenured Associate Professor in 2012 in the School of Design. As a graphic design major, Stacie spent the majority of her time in the Margaret Morrison building. “We didn’t have laptops back then, so we spent most of our time in the Reese [Computer] Cluster. I grew up as a designer and person in that space.” After Stacie got her masters at NC State University, she was thrilled to return to her alma mater to teach, research, and practice design. “There’s so much life here,” she said. “The energy is contagious and unlike anything I’ve experienced anywhere else.”

Patricia Kenner, a honorary Maggie Murph and current Carnegie Mellon board member, graduated from the school in 1966. An arts lover, she was drawn to the university because of its mix of liberal arts and theater. She spent every Saturday morning practicing calligraphy on campus. All the while, she studied French, and served as president of her sorority.

Patricia has stayed highly involved in Carnegie Mellon affairs, with a special interest in keeping the Maggie Murphy women’s legacy alive. “I had the most marvelous experience here,” she said. “I want to do everything I can to give back to the current and future students.” Her promise has been realized across campus, including her work to establish the Maggie Murph Cafe in the Hunt Library and two benches near the tennis courts dedicated to friends in Margaret Morrison.

Margaret’s courage, to move her family across the Atlantic to find work, is echoed in the stories of these women and many others in the Carnegie Mellon community. From trade to liberal arts, policy and sciences, Margaret Morrison Carnegie Hall has educated women across disciplines for more than one hundred years. It may not be a coincidence that today, designers hold the keys to Margaret Morrison Carnegie Hall. Professor and theorist Herbert Simon said, “To design is to devise courses of action aimed at changing existing situations into preferred ones.” Interdisciplinary and future-focused, designers at Carnegie Mellon are risk takers and problem solvers working to devise a more opportune future – just as Margaret Morrison did for her family.