Designing the Hyperloop at Carnegie Mellon University

An Interdisciplinary team of more than 60 Engineers, Designers, and Business students from Carnegie Mellon University are working on changing the face of transportation.

In 2013, Elon Musk first communicated his idea for the Hyperloop, a new ultra-high speed ground based transportation network of tubes that could span hundreds of miles. With extremely low air pressure inside those tubes, pods filled with people would travel through them at transonic speeds. A Hyperloop pod could make the trip between Pittsburgh and New York City in just about half an hour at speeds of 300 miles per hour.

In order to make the idea of Hyperloop a reality, Musk and SpaceX announced a competition for university and other independent engineering teams to design and build the best pod for the Hyperloop.

“The real motivation is the impact this will have on people, cities and society,” said Anshuman Kumar, an Integrated Innovation master’s student, to Carnegie Mellon University’s The Piper. “Right now it’s a ‘vacation’ when a mother and father in Pittsburgh want to visit their daughter at college in New York. With the Hyperloop, it becomes as simple as ‘dinner in the city tonight.’ This is really about relationships and bringing people closer together.”

The Carnegie Mellon Hyperloop (CMH) Team is one of 22 finalist teams that were selected from over 1000 initial competitors during a SpaceX Design Weekend at Texas A&M this past January. The CMU team itself is comprised of sub-teams who coordinate with each other and collaborate on the various projects involved in the creation of the Hyperloop. The CMH Design team, specifically, is composed of BDes and BFA in Design students, a fifth-year architecture student, and Masters students from the Integrated Innovation Institute.

From a Design perspective, the Hyperloop presents a unique set of challenges and opportunities.

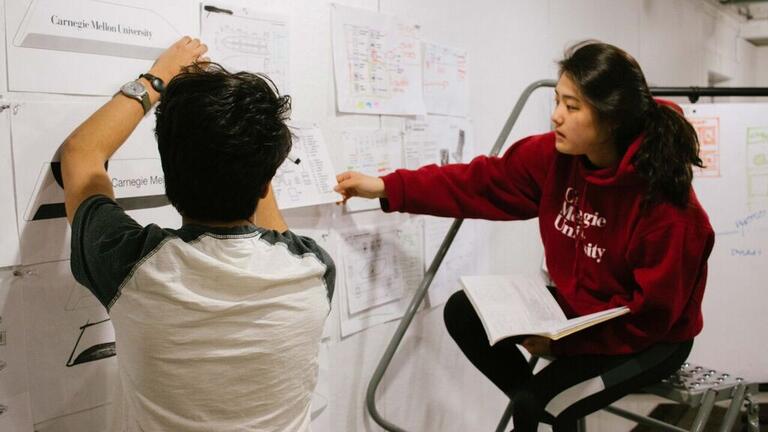

Because a majority of the work involves explanation of the pod's engineering principles and specifications, all design activities are preceded by a great deal of research. As such, it is imperative for the designers to coordinate with the engineering team, learning about the technical concepts and understanding how the pod would actually work. Design work on this kind of project can never be done in isolation.

Cameron Burgess, a first-year student at the School of Design, speaks to the relevance of his design education, that “learning about the utility of drawing to process and ideate has been invaluable.” While working on the Hyperloop project, designers often start on whiteboard or 11x17 paper to understand the key concepts to communicate. They then move to digital tools to render graphic assets for presentations and documentation.

Now, after presenting their designs to SpaceX in January, the CMU Hyperloop team is working towards building the final pod for competition at SpaceX’s HQ in the summer.

While the work of actually building the pod is underway, the CMH Design team is looking forward to the future of transportation in the context of the Hyperloop. The larger infrastructure that would be necessary to support it, the stations it would use and the smaller details of the Hyperloop pod interiors are all things that are being designed by the CMH team.

“We’re trying to consider the service design aspects of the experiences people would have with a Hyperloop-enabled future and the systems implications of a major infrastructure overhaul,” added Burgess.

“We are at the heart of innovation in transportation,” said Jacqueline Myra Yeung, a fifth-year Architecture and HCI student on the CMH Design team. “If Hyperloop became a reality, traveling the world would be at our fingertips.”

CMU Hyperloop proposes to help build a future where travel is more accessible, with more moments of wonder and fewer barriers and hurdles, and, as first year Bachelor of Design student Gautam Bose says “that problem is just as great a design challenge, as an engineering one.”

The CMU Team has just reopened their successful crowdfunding campaign after exceeding their original goal of $10,000, which enabled the team to build a foot-long working prototype. The additional funding will go toward the construction of the real pod, which will be entered into the SpaceX competition.