Matthew Wizinsky talks "Design After Capitalism"

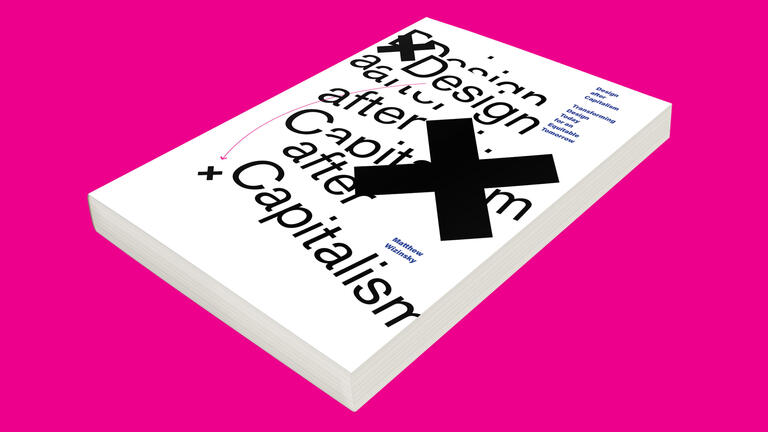

Matthew Wizinsky, a PhD Researcher from Carnegie Mellon University’s School of Design, recently published “Design after Capitalism: Transforming Design Today for an Equitable Tomorrow” with MIT Press. The book looks at how design can transcend the logics, structures, and subjectivities of capitalism: a framework, theoretical grounding, and practical principles.

The School of Design asked Matthew about his book, the inspiration behind it and the impact that designers can truly make.

By the time COVID-19 led to a nearly global shutdown, I had submitted a proposal to the MIT Press about a book that would critique design’s tight-knit relationship with capitalism and point toward some ways out. Because my children had been sent home from their schools and daycares, writing a book became a very daunting task. Yet, it also became the thing that I just HAD to do to get through 2020. During this time, we all had front-row seats to watch so much of our accepted knowledge about “how the world works” completely crumble right in front of our eyes. Systems broke, the impossible became normal, and then we could begin to see how things might be otherwise. Academic publishing takes time, so that book I wrote in 2020 was released in March, 2022. It’s called Design after Capitalism.

This book came about for a number of reasons. To start, I have been a designer for a long time. I have worked in small digital studios, startup environments, part of interdisciplinary teams in big international studios with global clients, and I’ve managed the design department for a large nonprofit organization. Eventually, I started an independent design studio, which is, in fact, a business. I start here because I think it’s important to note my proximity to “making a living” as a designer. This is something I know pretty well.

The 2008 financial crisis was a significant moment in my early design career. There was a sudden recognition of the massive shell game of the global economy. Yet, at the time, I felt ill-equipped to really confront design’s relationship to these issues. It was (and still is) hard to even see how much capitalism works as a kind of ideological container for even thinking about design.

As I moved more firmly into design education, I identified with the anxieties many students encounter between their desires to make change in the world as a "creative professional" and concerns over multiple contemporary crises. Not the least of these concerns are climate change and social inequity, both of which I believe are inextricably connected to capitalism. Racial justice is also entangled in economic justice.

As I describe in the book, my turning point came in 2016. During the run-up to that very polarizing presidential election, a poll from the Harvard Institute of Politics revealed something I just couldn’t get out of my head. Among young American adults, a slim majority responded that they did not “support” capitalism. This was striking because I realized two things: 1) this was not a fringe sentiment; this was a mainstream concern 2) these young people included my students, the very people with whom I spend a great deal of my time, my joys and sorrows, and my hope for a better world.

In 2017, I began teaching a speculative design course titled “Design after Capitalism.” This course brought together students from Communication, Fashion, and Industrial Design to imagine what a postcapitalist world might look like and what roles design and designers might play in it. It was really hard! Yet, it was so engaging because it was so challenging— for me and the students. I could feel our collective “future imagination” growing through each class. I could also witness a slow erosion of some heavily built-in assumptions about design amongst all of us. I went on to teach the class for five years. Those classes and the incredible students who participated in them gave me the privilege to participate in profound conversations and debates that have informed my thinking about the topic. It’s safe to say that if it wasn’t for that class, I wouldn’t have written this book. It’s worth noting that some of those students went on to work at places like Google and Apple while others went on to work at 18F (digital services for the US government) and in various social organizations. (Hello to all the Spec City alum, and thank you!)

What cracked open for me through those discussions, among others, was a way to see design differently—to see it boxed in, in a way that I hadn’t previously appreciated. With those 3 words in mind—design, after, capitalism—I set out on a research project that gathered up material from a wide range of fields typically not visited by design students: economics and economic theory, political science, critical theory, political philosophy, sociology (particularly economic sociology), and various strands of digital media and digital culture studies. What I hope I’ve accomplished, if nothing else, is that by reading a WHOLE LOT of books outside of design, I’ve made those ideas relevant INSIDE design so that design students can think with them (without having to read ALL those books!). I really thought about design students the whole time I was researching and writing this book because I wanted it to work for them. To accompany the book, designaftercapitalism.org has digital tools to animate the book’s ideas both in teaching and in practice. These include lecture videos, reading lists, case studies, reading and teaching guides, and practical guidelines. There’s even a version of the book in memes. I hope the book and these extensions of it will inspire students—plus practicing designers and professionals and scholars in various fields that interface with design—to consider the “institutional” nature of design practices and how they might be more equitably and sustainably crafted. Design itself is synonymous with change. It is about materializing preferable states of the world and, in doing so, establishing preferable ways of being in that world.

Attempting to trace a path out of the current challenges facing design (and society) is, admittedly, a bold proposal. Some readers may find it unrealistic or disagree with my fundamental perspective. That's all fine and well! In fact, I think bringing those tensions into the light can help us all reckon with how design activities produce and reproduce certain social, political, and economic conditions. In my experience, this is largely invisible to most designers. My hope is that the book will empower designers to rethink and transcend some current modes of practice that are reinforcing detrimental social and political situations. I hope the book will offer some language, ideas, and perspectives that encourage designers and design students to better "think" how design interacts with economic and political structures beyond "business as usual."

I also hope designers can recognize their labor and access to decision-making is exactly where their power resides in systems that seem otherwise insurmountable. The book does NOT say, “hey, let’s overthrow everything and build a utopia.” Instead, it says, “let’s look at how we do what we’re doing and see if we can’t do better, to take account of the broader impacts of our work, our lives, our communities, and the kinds of ideas we create and circulate.” Beyond a critique of “business as usual,” I provide practical guidelines for designers to use collectively in determining the ways that design itself might come into a preferred state—starting now and working into the future.

The book is the foundation for the work I hope to do as a PhD researcher in Transition Design. There is no other program in the world that is so well aligned with my interests, particularly as it sees “design” as a central actor in long-term social transitions (whatever new things that term may mean in the coming decades). We can’t “fix” so many of the challenges that matter most today with “solutions” that are limited to very short-term results for a very narrow swath of humanity (or the planet). We have to think bigger and longer-term, but we also have to dig in more deeply and commit ourselves locally. We have to be more accountable, not only to the people we consider clients but to a much broader community of “we.” This is what Transition Design proposes we can, and perhaps must do. This is a big pivot for the profession we have called “design” for about a century now.

It’s funny: While writing the book, I was taking a walk in my neighborhood one day (Northside in Cincinnati, OH). I saw some graffiti that has stuck with me. Someone wrote “Fuck Capitalism” on a wall. Of course, that caught my eye. Right next to it, someone else came along and wrote: “We Are Enough.” I think about those three words just about every day now. I’m trying to adopt the positive language of “We Are Enough” while finding and demonstrating ways that design can prove just that.

Matthew Wizinsky is a designer, educator, researcher, scholar, and a lecturer on contemporary design practices and research. He was formally trained in graphic design at the University of Cincinnati (BS), the University of Illinois at Chicago (MFA), and the Institute of Visual Communication (FHNW) in Basel, Switzerland, and holds professional certification in strategic Foresight from the University of Houston.

On May 6th, the School of Design will host an online talk about Design After Capitalism with Matthew Wizinsky and School of Design Doctoral Alumnus Dimeji Onafuwa, as part of Design Week for Spring 2022.